k-Nearest Neighbours (kNN): From Clinical Similarity to Safe Missing-Data Imputation

- Mayta

- Dec 28, 2025

- 6 min read

Introduction

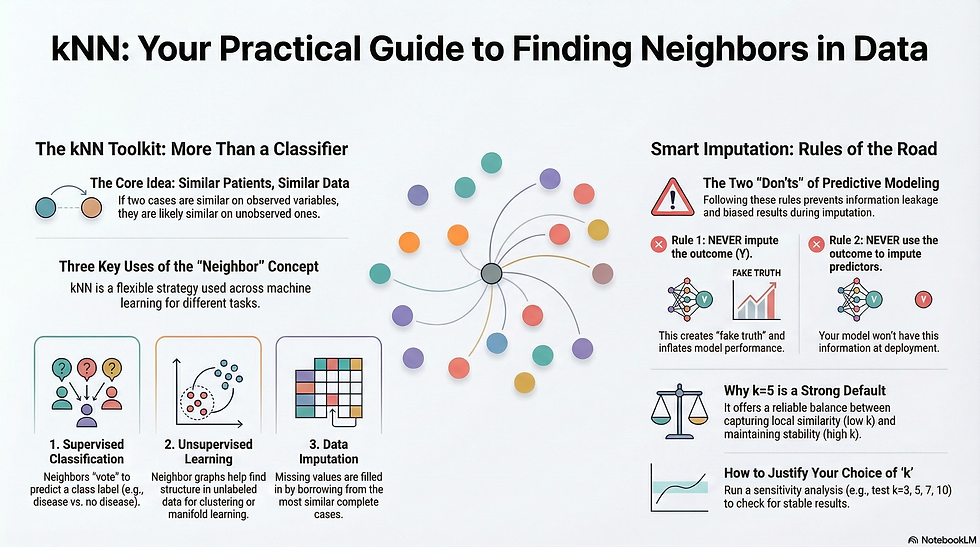

k‑Nearest Neighbours (kNN) is one of those rare methods that shows up everywhere in machine learning and clinical data science—not because it is “fancy”, but because the core idea is extremely reusable:

If two patients look similar on the variables you can see, they are likely to be similar on the variable you can’t see.

That “variable you can’t see” might be a class label (disease vs no disease), a numeric outcome (e.g., risk score), or simply a missing lab value that needs imputation.

This article explains what kNN is, how it connects to unsupervised learning / clustering, and how to use it safely for missing‑data imputation (including why we do not impute the outcome Y).

1) The core concept: neighbours in feature space

Every observation (patient) is a point in a multidimensional space:

axes = predictors (age, sex, labs, symptoms, etc.)

distance = how “close” two patients are, based on those predictors

kNN is not one single algorithm; it’s a neighbourhood idea:

Pick a distance function.

For a given patient, find the k nearest neighbours.

Borrow information from those neighbours.

That’s it.

2) kNN in machine learning: supervised vs “unlabelled” uses

A) Supervised kNN (needs labels)

This is the classic “kNN classifier / regressor”.

kNN classification: neighbours vote (majority vote) → predicted classExample: GI malignancy vs non‑malignancy.

kNN regression: average (or weighted average) neighbour outcomes → predicted valueExample: predict HbA1c.

Here you must have labels (Y known in training data). This is supervised learning.

B) Unsupervised / “unlabelled” neighbour methods (no labels needed)

Your professor’s point about “unlabelled / clustering” is also valid—the neighbour idea is used inside unsupervised learning, even if the classic kNN classifier is supervised.

Examples:

kNN graph: connect each point to its k nearest neighbours → a graph.That graph is used in:

spectral clustering

manifold learning (Isomap, UMAP‑style neighbourhood graphs)

density / neighbourhood methods: DBSCAN and related methods rely on neighbourhood density (not exactly kNN, but same “who is near me?” concept).

outlier detection: points with very distant neighbours can be anomalies.

So yes: the kNN neighbourhood idea is often “unlabelled”.But be careful: kNN ≠ k‑means.

k‑means = clustering algorithm (find K cluster centres)

kNN = neighbour lookup rule (find k neighbours)

3) kNN for missing‑data imputation: why it works

What is kNN imputation?

kNN imputation fills in missing values by looking at patients who are similar on observed variables.

For each missing cell:

Identify neighbours using the other observed predictors.

Impute:

continuous → median (robust) or mean

categorical/binary → mode (most common category)

This is conceptually similar to “hot‑deck” imputation in epidemiology: replace missing with values from similar donors.

Why kNN imputation is attractive

Simple

Works with mixed data types (continuous + categorical)

Preserves realistic values (imputed values come from real patients)

Practical when MI is unstable or too complex

But: kNN imputation is still “single imputation”

This means it creates one completed dataset. It does not automatically reflect uncertainty the way multiple imputation does. So:

Great for model development workflow and operational prediction pipelines

Needs caution for formal inference (SEs, p‑values)

(If your goal is prediction modeling, this is usually acceptable with clear reporting + internal validation.)

4) Why we do NOT impute Y (the outcome)

In prediction modeling, there are two common “don’ts”:

✅ Don’t impute the outcome (Y)

If Y is missing, imputing it creates “fake truth”. It can:

distort prevalence

bias model training

create false performance

✅ Don’t use outcome information to fill predictors in a way that won’t exist at deployment

If your goal is to build a model that will be used on new patients (where Y is unknown at prediction time), then imputing predictors using Y can be seen as information leakage.

In our clinical prediction workflow guidance, the rule is:

Prediction models: impute X, not Y; avoid using outcome Y for imputation.

That’s the clean “deployment-safe” principle: the imputation step should not rely on information that won’t be available when the model is used.

5) Why use RAW predictors (no transformations) before kNN imputation?

When people say “raw predictors only”, they usually mean:

do not create derived predictors first (e.g., wbc_k, plt_100k, polynomial terms, post‑test variables, diagnosis results)

do not inject downstream information (endoscopy/pathology results) into X when your model is meant to predict before those tests

This is correct and important for clinical prediction modeling:

keeps clinical interpretability

prevents target leakage

imputation uses the same predictors you will have in real practice

One technical note: many kNN implementations internally standardize variables for distance calculation (so labs with large scales don’t dominate distance). That scaling is not “feature engineering” in the clinical sense; it’s just making the distance computation fair.

6) Is k = 5 a “magic number”?

The honest answer: k = 5 is a strong default, not magic.

k is a bias–variance trade‑off:

Small k (1–3)

captures local similarity− unstable, sensitive to noise/outliers

Large k (10–30+)

more stable− can oversmooth (patients no longer “similar enough”)

Why k = 5 is commonly used

Because it often balances:

stability (not too noisy)

locality (still “similar” neighbours)

speed (computationally reasonable)

That’s why many teams standardize on k = 5 for baseline kNN imputation in clinical datasets.

How to choose k properly (blog‑friendly methods)

Method 1: Sensitivity analysis (fast and practical)

Run imputation with a few k values and compare:

distributions (histograms/boxplots)

model performance (AUC, calibration slope)

key coefficients stability

Typical set: k = 3, 5, 7, 10

If results are stable, k = 5 is defensible.

Method 2: “Mask-and-recover” tuning (more technical, more convincing)

You can simulate missingness:

randomly hide a small fraction of observed values

impute them using different k

compare imputed vs true values (RMSE for continuous, accuracy for categorical)

pick the k with smallest error

This is one of the cleanest ways to justify k.

7) Practical R template: kNN imputation for real clinical data

Below is a general template (works for many projects).Key rules included: exclude ID, exclude outcome, impute only predictors.

library(haven)

library(dplyr)

library(VIM)

df <- read_dta("your_data.dta")

id_var <- "ID"

y_var <- "outcome"

X_vars <- c("age","sex","hb","wbc","plt","fit") # <- choose your predictors

X <- df %>%

select(all_of(X_vars)) %>%

mutate(across(where(is.labelled), as.factor)) # Stata labelled → factor

set.seed(215)

X_imp <- kNN(

X,

k = 5,

imp_var = FALSE,

numFun = median,

catFun = maxCat

)

df_imp <- bind_cols(

df %>% select(all_of(c(id_var, y_var))),

X_imp

)

8) Code to “tune k” using mask‑and‑recover (blog‑ready)

This gives you a defendable reason for k = 5 (or shows another k is better).

library(VIM)

library(dplyr)

score_knn_k <- function(X, k, p_mask = 0.10, seed = 1) {

set.seed(seed)

X0 <- X

# locate observed cells

obs <- which(!is.na(as.matrix(X0)), arr.ind = TRUE)

# mask a subset

n_mask <- floor(nrow(obs) * p_mask)

idx <- obs[sample(seq_len(nrow(obs)), n_mask), , drop = FALSE]

X_mask <- X0

true_val <- vector("list", n_mask)

for (i in seq_len(n_mask)) {

r <- idx[i, 1]; c <- idx[i, 2]

true_val[[i]] <- X_mask[r, c]

X_mask[r, c] <- NA

}

# impute

X_imp <- kNN(

X_mask,

k = k,

imp_var = FALSE,

numFun = median,

catFun = maxCat

)

# evaluate

num_cols <- which(sapply(X0, is.numeric))

cat_cols <- which(sapply(X0, function(z) is.factor(z) || is.character(z)))

# collect imputed vs true

rmse <- NA

acc <- NA

# numeric RMSE

if (length(num_cols) > 0) {

num_idx <- idx[idx[,2] %in% num_cols, , drop = FALSE]

if (nrow(num_idx) > 0) {

true_num <- sapply(seq_len(nrow(num_idx)), function(i){

r <- num_idx[i,1]; c <- num_idx[i,2]

X0[r, c]

})

imp_num <- sapply(seq_len(nrow(num_idx)), function(i){

r <- num_idx[i,1]; c <- num_idx[i,2]

X_imp[r, c]

})

rmse <- sqrt(mean((as.numeric(imp_num) - as.numeric(true_num))^2, na.rm = TRUE))

}

}

# categorical accuracy

if (length(cat_cols) > 0) {

cat_idx <- idx[idx[,2] %in% cat_cols, , drop = FALSE]

if (nrow(cat_idx) > 0) {

true_cat <- sapply(seq_len(nrow(cat_idx)), function(i){

r <- cat_idx[i,1]; c <- cat_idx[i,2]

as.character(X0[r, c])

})

imp_cat <- sapply(seq_len(nrow(cat_idx)), function(i){

r <- cat_idx[i,1]; c <- cat_idx[i,2]

as.character(X_imp[r, c])

})

acc <- mean(imp_cat == true_cat, na.rm = TRUE)

}

}

tibble(k = k, rmse = rmse, acc = acc)

}

# Example usage:

# X must be your predictor-only data frame (no ID, no outcome)

# ks <- c(3,5,7,10)

# results <- bind_rows(lapply(ks, function(k) score_knn_k(X, k, p_mask = 0.10, seed = 215)))

# results

How to interpret:

Lower RMSE = better numeric imputation

Higher accuracy = better categorical imputationIf k = 5 is near-best and stable → you can say “k = 5 was selected as a robust default, supported by sensitivity analysis.”

9) Common pitfalls (the things that break kNN)

Including post‑diagnostic variables in X (endoscopy results, pathology, final diagnosis)→ leakage (predicting with information from the future)

Including the outcome (Y) for imputation in prediction modeling→ breaks deployment logic and inflates performance

Too many predictors with weak signal→ distances become meaningless (curse of dimensionality)

High missingness in many predictors→ neighbour search becomes unreliable(kNN is strongest when most predictors are observed)

Not checking pre/post distributionsAlways check that imputation did not create impossible values or distort prevalence.

10) A clean blog conclusion you can reuse

kNN is not only a “classifier”. It is a general neighbourhood strategy used across machine learning:

supervised: classification/regression (needs labels)

unsupervised: neighbour graphs and density concepts used in clustering/manifold learning

data engineering: missing‑data imputation using “similar patients”

Using k = 5 is a strong practical default, but the best workflow is:

start with k = 5

run sensitivity analysis (k = 3,5,7,10)

optionally justify k using a mask‑and‑recover experiment

Comments